29 August 2024 by Anne Sarzin

Read on for the article

A book review by Anne Sarzin

With my back pressed against a tin hut, I stared at the mob coming towards me in panic.

It was January 1995 and I was with a group of journalists in the township of Zwide on the outskirts of Port Elizabeth, waiting for President Nelson Mandela to inaugurate a sewage project as part of a reconstruction and development programme for the city. Fortunately, the chanting and swaying crowd stopped just inches from us to watch the President symbolically shovel a few spades of red earth into a ditch. Then his security men led him away.

It was the only moment of fear in a day spent following the President’s every move – from Dan Qeqe Stadium to the Sisonke Community Centre in Zwide, the sewage ditches on Mbilini and Tunyiswa roads and finally to Dan Adcock Stadium. At the top of a packed gallery, I listened to the President speak in Afrikaans, Xhosa and English. Surrounded by a black sea of cheering faces, the air echoing with shouts of “Viva Mandela”, I felt relaxed and at ease despite my brief moments of fear earlier that day. At a press conference earlier in the day, I had the privilege of meeting President Mandela, who was approachable, warm, friendly and dignified. When I told him I was now living in Sydney, Australia, he said, “Say hello to Bob (Hawke) and Paul (Keating) for me”, which I regretfully never did.

Miraculously, the transition to democracy last year was relatively peaceful, with voices of reconciliation heard from all sides. South Africans wanted to heal old wounds, and a new agenda seemed to be taking shape, with freedom and equality enshrined in the interim constitution. Mandela declared that he would not tolerate attempts to undermine democracy through anarchy and lawlessness, and he committed his government to reducing crime. He also promised to overhaul the judiciary, establish a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, end political violence in Kwazulu Natal, and create jobs and economic growth.

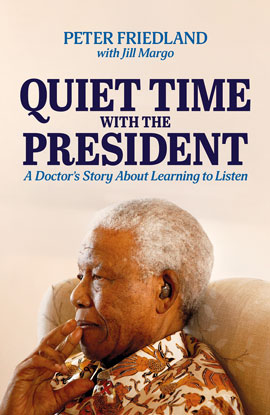

Now, remembering my momentous encounter with the great Mandela 29 years ago, I turned to the book with great anticipation. Quiet Time with the President: A Doctor’s Story of How He Learned to Listenco-authored by Professor Peter Friedland and his sister Jill Margo, a well-known journalist in Sydney. I was not disappointed. This memoir is a touching, honest, informative and indeed fascinating portrait of Mandela, told in the context of South Africa’s emerging democracy. It is a powerful story, with the charismatic Mandela at its centre, tracing Mandela’s rise to power amid the euphoria and optimism of his early years as president, and describing with respect and compassion his subsequent decline – both political and physical – and its impact on his legacy. While Mandela was celebrated internationally, there were critics at home who belittled his standing in the eyes of his people, accusing him of not moving forward or realising the rainbow nation’s aspirations quickly enough. Not least among them was Thabo Mbeki, who succeeded him as president in 1999 and, as Friedland notes, may have been jealous of Mandela’s status as a globally revered statesman. Mbeki marginalized Mandela’s involvement in the country’s affairs at home and abroad, which hurt Mandela, who had great respect for Thabo’s father, Govan Mbeki, and maintained an enduring friendship with him. He (Thabo) was imprisoned with Mandela on Robben Island. “He (Thabo) wants the ‘old man’ to mind his own business,” Mandela said. Consequently, Friedland said, while he retained his international standing, his involvement was no longer as pronounced.

Now, remembering my momentous encounter with the great Mandela 29 years ago, I turned to the book with great anticipation. Quiet Time with the President: A Doctor’s Story of How He Learned to Listenco-authored by Professor Peter Friedland and his sister Jill Margo, a well-known journalist in Sydney. I was not disappointed. This memoir is a touching, honest, informative and indeed fascinating portrait of Mandela, told in the context of South Africa’s emerging democracy. It is a powerful story, with the charismatic Mandela at its centre, tracing Mandela’s rise to power amid the euphoria and optimism of his early years as president, and describing with respect and compassion his subsequent decline – both political and physical – and its impact on his legacy. While Mandela was celebrated internationally, there were critics at home who belittled his standing in the eyes of his people, accusing him of not moving forward or realising the rainbow nation’s aspirations quickly enough. Not least among them was Thabo Mbeki, who succeeded him as president in 1999 and, as Friedland notes, may have been jealous of Mandela’s status as a globally revered statesman. Mbeki marginalized Mandela’s involvement in the country’s affairs at home and abroad, which hurt Mandela, who had great respect for Thabo’s father, Govan Mbeki, and maintained an enduring friendship with him. He (Thabo) was imprisoned with Mandela on Robben Island. “He (Thabo) wants the ‘old man’ to mind his own business,” Mandela said. Consequently, Friedland said, while he retained his international standing, his involvement was no longer as pronounced.

In this book, Friedland primarily tells the story of his professional relationship with Mandela as his ENT specialist, monitoring his increasing hearing loss and, at times, his general health over several years. While Friedland modestly claims he never overstepped the boundaries of their professional relationship as doctor and patient, it is clear that these two men shared a friendship that was important to both of them and that flourished over countless cups of tea in Mandela’s Houghton home, with breaks in which Mandela embodied the wise mentor and Friedland his young and admiring pupil. “He told me a story from which I had to guess the lesson,” Friedland recalls. “He operated on a different plane, concerned with principles and politics, not the small twists and turns of people’s lives.” Friedland speculates that this may have been the result of 27 years of isolation, living exclusively with men and not in a family or community where these concerns were part of everyday conversation.

For the Jewish reader, there is an interesting account of Mandela’s views on the Middle East, where many of his enduring friendships with actors in the region, such as Arafat, were based on the years of support they gave to the ANC. “Remember that your enemy is not necessarily my enemy,” he warned Friedland. “You have the right never to forget, but you must forgive in order to move forward.”

Friedland’s own story – of the challenges of his childhood, his military service and his traumatic experiences of losing close friends murdered by gangsters riding South Africa’s crime wave – is compelling in its honest assessment of the violence and deteriorating situation in the country and the resulting fear that undermines the quality of life of those barricaded behind high suburban walls. His decision in 2009 to emigrate to Australia with his young family was not an easy one, and he dreaded telling Mandela, who had always put his country before his family. “My memory of those last years is clouded with sadness … he spent so much time away from his loved ones and then had no time to repair his neglected relationships,” Friedland notes. “Although being swept up in the common good was glorious and politically fulfilling, it was also emotionally impoverished.”

It is clear that Friedland’s priorities were clearly on the safety and future well-being of his family. After moving to Perth, he established himself as a leading ENT surgeon and university lecturer. But it was a story Mandela told him before they parted that set him on a path he might not otherwise have taken after arriving in Australia. Readers will discover this anecdote and Mandela’s parting advice to his doctor for themselves. Friedland and Margo worked seamlessly together as co-authors and they are to be congratulated on this well-crafted and touching tribute to Mandela, as well as on their sensitive story of migration with all its challenges.

Quiet Time with the President: A Doctor’s Story of How He Learned to Listen

Published by:

Jonathan Ball

Cape Town and Johannesburg