In the series “We the People,” The Spokesman-Review examines a question from the naturalization test that immigrants must pass to become U.S. citizens.

Today’s question: What was the Great Depression?

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, money was tight for the American working and middle classes—so money for non-essentials, including the arts, dried up as people saved what they could.

“It was a real tragedy on many levels,” said Matthew Sutton, a history professor at Washington State University. “Not only were Americans struggling with unemployment and hunger and fear of what was happening at home and abroad, but they were also losing those little moments of escape.”

President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal attempted to stabilize the American economy and society.

“The policies of the New Deal saved many people from poverty and hunger,” said author and journalist Timothy Egan. “It brought us welfare for the elderly and agricultural subsidies for those who were driven off their land because they couldn’t pay their taxes or mortgages.”

Massive losses in share prices are often one of the first bad signs of a weakening economy, as was the case in 2008 during the so-called Great Recession and in 1929 during the Great Depression.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average lost more than 1,000 points last Monday. This came after the Dow had fallen more than 1,000 points in the previous two days. It has since partially recovered, but the decline has led some to speculate that America could be sliding into a recession.

The economic collapse that followed the stock market crash of 1929, which led to the Great Depression, was characterized by high unemployment, low financial stability, and an uncertain future. In Eastern Washington, the agriculture-dependent economy suffered greatly from the crisis.

In 1938, the Work Progress Administration opened the Spokane Art Center, one of many art centers across the country. The goal was to ensure that the American people did not lose a generation of artistic talent and that artists continued to have work.

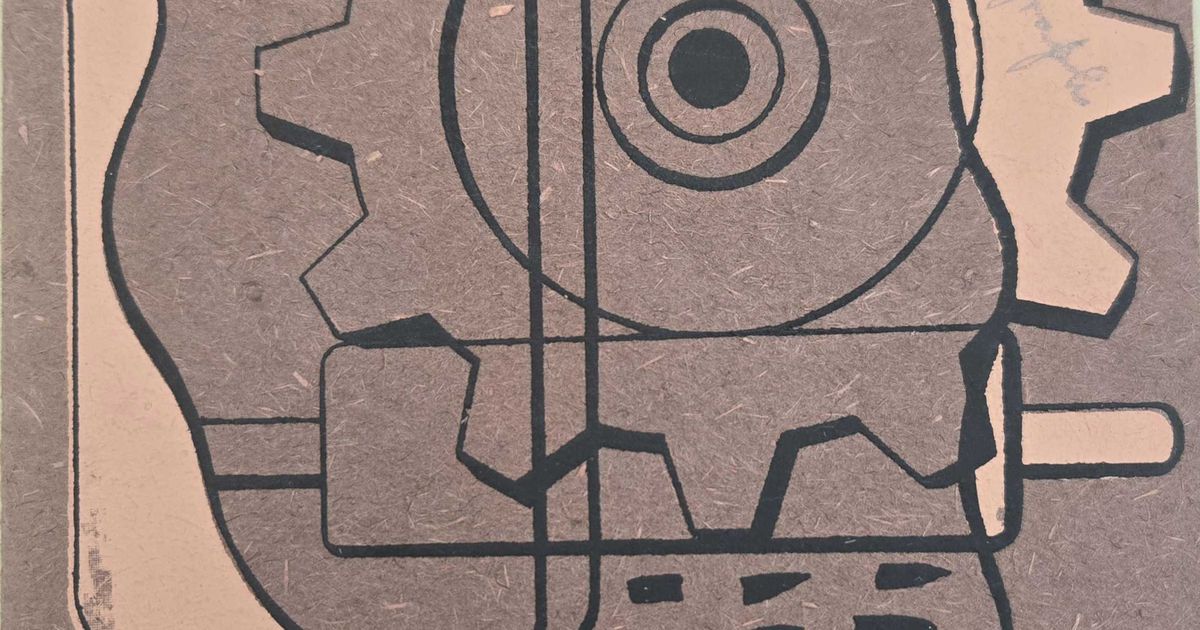

The center quickly became a pillar of the community and the art world at large, with people from all walks of life attending free classes that taught art history and artistic skills such as painting, sculpture, and lithography.

The center’s staff included renowned artists from across the country: Carl Morris, Guy Anderson, Z. Vanessa Helder, and Robert Engard, to name a few.

The well-known abstract expressionist Clyfford Still frequently visited the center and even exhibited there. Still’s art was particularly influenced by the Depression.

“We see him expressing himself in his more representational works of figures who were oppressed or really struggling given societal circumstances,” said Bailey Placzek, curator of collections, catalog raisonné research and project manager at the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver. “That experience of taking what he saw in the hardship around him and turning it into art really drove his art.”

The work of the art center’s teachers and contacts had a major influence on the later development of the Northwest School of Art.

Despite the positive reception by the community and the high caliber of staff and students, the center always had problems with funding and a high turnover of staff. The entry of the United States into World War II was the final blow, as the community’s attention was diverted to the war effort.

Although the original center no longer exists, its tradition of arts education continues today at the Corbin Art Center, where children and adults can participate in arts and culture classes.

The Corbin Art Center opened in 1952 as the Spokane Art Center under the direction of Washington State University. The new center was a great success for the community for years until WSU terminated the project in 1965. An initiative then began to restart the program at the Corbin House as part of the city’s Parks and Recreation Department, where it has been housed ever since.

The Corbin Art Center’s art programs include all types of media – painting, drawing, writing and more. In the years following the COVID-19 lockdowns, demand has only increased.

Ryan Griffith, assistant director of recreation at Spokane Parks, described the recovery as “almost like a renaissance where everyone came back together and really started saying, ‘This is what I’ve been missing in my life.'”

It is no coincidence that both centers gained great popularity after a crisis across the country. Hard times inspire people to new ideas.

“Hard times bring about creative times for writers, artists and filmmakers,” Egan said. “An extraordinary amount of cool, creative stuff has come out of the Depression.”

Griffith said it was about more than just the art itself.

“Art is a wonderful way for adults and teens to escape from the screen or just the hustle and bustle of everyday life,” Griffith said. “It gives them a chance to relax. It gives them a chance to be creative and to be around other people who want to do the same thing.”

Placzek agreed, saying art gives people the opportunity to discuss difficult issues and build community.

“Art provides a real starting point for discussion, but also a refuge,” says Placzek. “It helps us to connect with each other over time. It helps us to see that others have gone through and overcome the hardships and struggles we are currently experiencing. And it helps us to feel part of a larger society. And it reminds us of our humanity and what makes us human and what connects us.”

Placzek said it was critical that communities provide resources and opportunities for the arts — which is exactly what art projects did during the Great Depression. New Deal art initiatives like the Spokane Art Center put art in people’s hands, which changed 20th-century American art.

“It really broadened the audience because suddenly you didn’t need money to see the orchestra,” Sutton said.

“So it’s actually had a positive impact and has introduced the arts to a whole new generation that might not have been accessible to them otherwise.”