On August 19, 1874, Irish physicist John Tyndall – today better known as a co-founder of climate research – spoke for almost two hours to 2,000 people at the Ulster Hall in Belfast. His statement sparked one of the most heated controversies about science and religion in modern times. The repercussions are still felt today.

Tyndall’s three main arguments threatened deeply held religious beliefs. The first was that only science was competent enough to speak about the material world. The second was that the physical universe contained the “promise and power” of life, consciousness, and reason. The third was that religious believers had no reason to claim they had definitive knowledge of the unfathomable mystery at the heart of existence.

The tension between Tyndall’s vision of science and religion and that of many of his Victorian contemporaries had been building for decades. His highly acclaimed lecture was intended to increase the pressure to breaking point.

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution was a powerful tool for Tyndall to pursue this goal. For Tyndall, Darwin offered a convincing natural explanation for the diversity of life on Earth and made the idea of divine intervention superfluous. While Darwin was reluctant to make firm claims about the beginning of life, Tyndall was not so reluctant. There was no time in the history of the cosmos, Tyndall explained, when “creative acts” by a “deity” were required.

Two remarkable phenomena emerged: human cognition and consciousness. Tyndall fully recognized what has since been called “the hard problem” of consciousness: how subjective experience is derived from non-conscious matter. But he was convinced that knowledge of the gradual development of cognition, a more advanced science of the brain, and a redefinition of matter would provide a natural explanation of the human mind.

Reactions to Tyndall’s explosive lecture were not long in coming. While his Belfast audience applauded politely, physicist Oliver Lodge recalled that the atmosphere had become “more and more sulphurous.” Editorials in the press the next morning raised the alarm, and within days articles and letters to the editor denouncing the physicist’s misguided materialism (the theory that only physical matter exists) appeared in newspapers across the country.

In the weeks that followed, the backlash grew. On the Sunday after the lecture, Belfast’s pulpits “thundered” at him, as Tyndall put it. In late October, the bishops of the Catholic Church in Ireland published a letter half as long as Tyndall’s address, condemning his materialist metaphysics. At about the same time, prominent Presbyterians in Belfast organized a series of lectures to combat Tyndall’s philosophy of mind and nature.

In the years that followed, numerous articles, pamphlets and books were published analyzing Tyndall’s lecture. Many, if not most, accused Tyndall of abusing his prominent position to support an irresponsible materialism that undermined morality and the Christian religion.

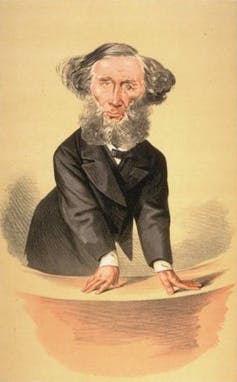

WikipediaCC BY-SA

Publicly, Tyndall responded to charges of atheism and crude materialism by vigorously denying that he held either. Contrary to what his critics thought, he did not reject “the facts of religious feeling.” Instead, he considered them “as certain as the facts of physics.” What he did reject was the translation of subjective religious inclinations into fixed theological convictions. Dogmatic religion, he argued, was the enemy of science and of a better future.

In private, he reacted more violently. As his now published correspondence from 1874 shows, one attack made him consider legal action. In fact, he only abandoned this approach when he was told that it was unlikely to succeed.

Ongoing debate

A century and a half later, Tyndall’s main theses are generally accepted where they were once hotly contested. Religion, as Tyndall understood it, remains an important, if rather private, part of people’s lives. But his allergy to religious certainties is commonplace today.

However, his arguments continue to be challenged. His philosophy of science and his understanding of religion, while widely popular, still have serious critics. His account of the development of science, which was already ridiculed by astute critics such as the religious scholar William Robertson Smith in 1874, is no longer supported by professional historians.

Apart from the chronological confusion and anachronistic representations of various philosophical schools, Tyndall’s emphasis on the importance of individual “men of extraordinary power” for the progress of science is no longer considered tenable. His representation that dogmatic religion everywhere hinders scientific progress is also the subject of ongoing criticism.

The scientific racism that helped underpin Tyndall’s explanation of the origins and evolution of the human mind (Tyndall appealed to alleged differences in brain size between the “savages” of his time and Europeans to support his claim that the human mind had evolved) has also been thoroughly discredited, although, disturbingly, it has not yet been completely eradicated.

In other areas, such as the origin of life, scientific research has made significant progress, although of course questions remain. Tyndall’s advocacy of a kind of “panpsychism” – the idea that consciousness is already built into matter – has recently been revived, although this remains a minority view among consciousness researchers.

Whatever its strengths and weaknesses, Tyndall’s Belfast speech dramatically shifted the dividing lines between science and religion in ways that continue to shape our discussion of them today. In particular, the largely materialist explanation of mind and consciousness that Tyndall advocated continues to generate heated debate.

If you have a few hours to spare, Tyndall’s infamous lecture is definitely worth reading.