“I’m not half Japanese and half British; I’m both.”

Duncan Ryuken Williams grew up in Japan and the UK, living between cultures, languages and religions. He never felt like he really belonged anywhere. When he came into contact with the Buddhist concept of the Middle Path, he felt relief that these spaces in between could actually be the basis for freedom and connection.

Ruth Ozeki had a similar experience growing up as a mixed race woman: “I always felt pulled in two directions, I was not at home in any one place and always in between.” For Ozeki, a New York Times As a bestselling author, filmmaker, and priestess of Zen Buddhism, The Middle Way offered a broader approach to questions of identity, and in her novels she uses writing as a means to explore the nature of suffering and the self.

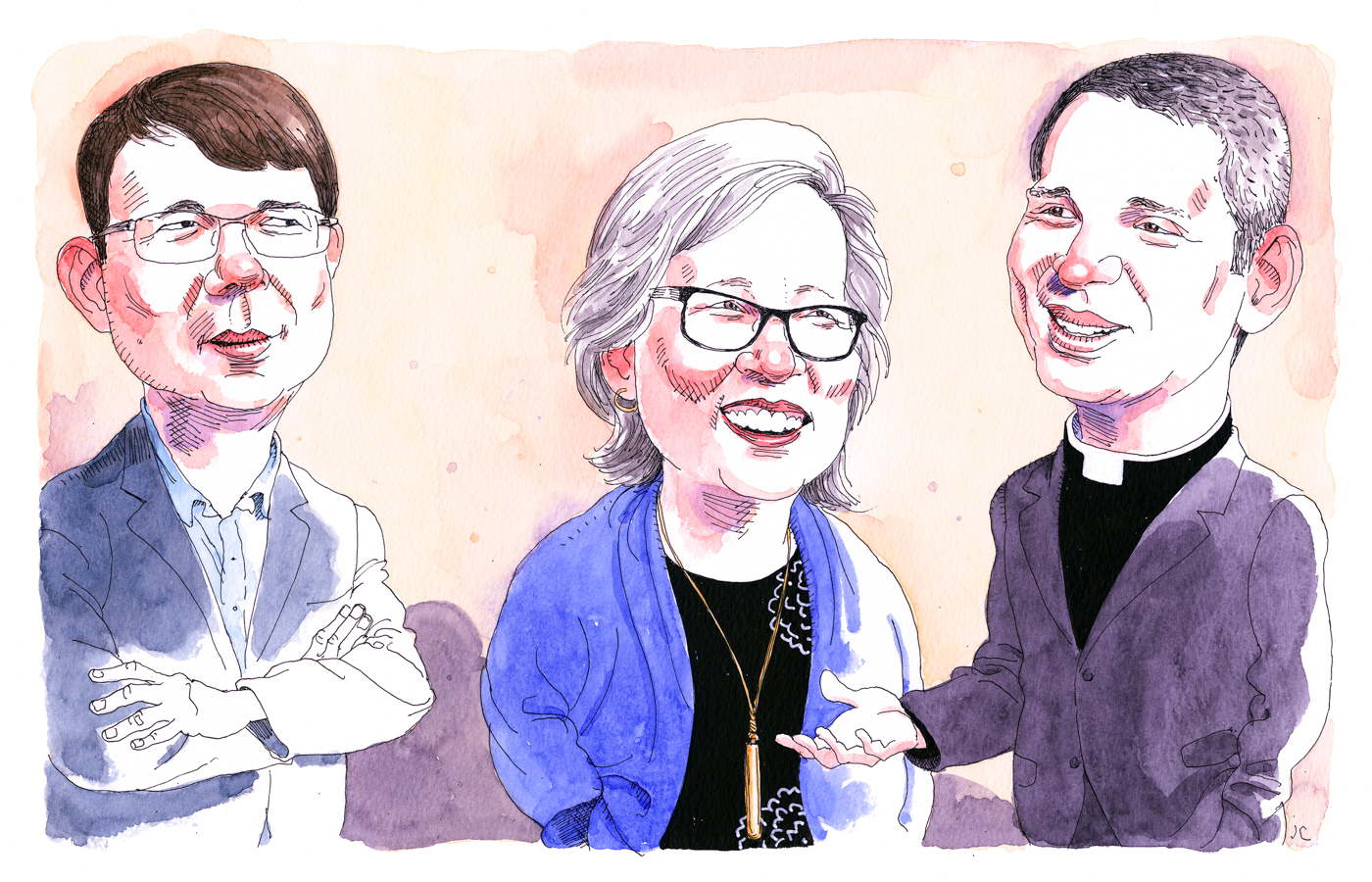

Recently, Ozeki and Williams spoke with the Reverend Matthew Ichihashi Potts, Plummer Professor of Christian Morality at Harvard Divinity School (and himself mixed race), to discuss the liberating power of in-between states, the role of storytelling in alleviating suffering, and the parallels between the Four Noble Truths and the project of literature.

Matthew Ichihashi Potts (MIP): I want to start with the question of identity as a mixed race person. Before I knew you, Ruth, I had a feeling of recognition in your characters. I also know that there is more going on in your novels than this shock of recognition – it is about the diversity of identities in a broader and more central sense. Can you say something about that?

Ruth Ozeki (RO): Sure, it’s a big topic, and it’s a very Buddhist topic. It took me a long time to understand how to write a novel, precisely for this reason (because I was grappling with questions of identity and recognition). The novels I read as a child were usually written by white authors with a Eurocentric position. The Warrior was published when I was in my twenties, and The Joy Luck Club was published when I was in my 30s, so I had no reference points as a kid.

I didn’t write my first novel until I was in my late 30s. My meat yearand I remember feeling compelled to have a white protagonist when I was writing the novel. One of the two protagonists was a documentary filmmaker who was caught between the cultures of Japan and the US, and so it just made sense from a racial perspective that the character was biracial. At first I resisted it (making her biracial) because I thought then everyone would think she was me. There’s something special about being biracial that means you can’t hide. If a white male author writes a book with a white male protagonist, readers aren’t going to immediately assume that the protagonist is the author. I made this character six feet tall and gave her green hair so people could tell us apart. (laughs)

The path is enormously wide and the way we define things is very narrow. The idea of ”normal” is a cultural construct.

MIP: One of the things I admire about your writing is your willingness to look directly at suffering and examine it closely. You deal with many forms of suffering in your novels, but the last two novels focus particularly on mental illness. Could you say more about that?

FR: I think there is such a parallel between Buddhist teachings and the project of literature. The first noble truth of Buddhism is the truth of suffering. When you think about literature, I challenge you to think of a novel that does not have suffering at its center. I think that the first noble truth of literature is also the truth of suffering, and so the two projects are not as different as they might seem.

The reason I write is exactly that: to examine a kind of suffering and really look at it. I’ve found that if I don’t make something a project, I tend to ignore it, and so with my last two books I wanted to look back at my own past and understand why I was so unhappy as a young person. I wanted to understand, for example, why I had all kinds of suicidal thoughts when I was 16. That’s something I share with my protagonist in A story for the moment.

Duncan Ryuken Williams (DRW): Let’s go back to the question of mixed-race identity. When I grew up in Japan, I didn’t fit in because I didn’t look Japanese enough, but when I went to the UK, I didn’t fit in there either. I grew up not really belonging anywhere, feeling caught between cultures, languages and even religions.

When I was thinking about becoming a Buddhist priest, I was struck by the idea of the Middle Path, or the idea that liberation is not found on one side but in between. That way, I didn’t have to choose a single path: I could embrace everything by being in the middle. Being of mixed descent, I was drawn to the very first question in Dogen’s Genjokoan: who am I“This investigation led me to study Buddhism.

FR: I’m so glad you bring this up, because growing up I always felt pulled in two directions, at home in neither place, always in between. The idea that there was a religious tradition that taught the Middle Way was a huge relief—suddenly there was something bigger than the feeling of being neither here nor there, something more all-encompassing, to use another of Dogen’s phrases.

The path is enormously wide and the way we define things is very narrow. The idea of ”normal” is a cultural construct. It’s a fiction – we invented it. And since we invented this idea of ”normal” in the first place, why can’t we just expand it to make it more all-encompassing, to make it big enough to include all of us?

This all comes from Genjokoan’s instruction to study the self. It is such a profound teaching. If I had to name one teaching as the lamp for me, it would be this one.

MIP: Ruth, how do you think about the relationship between your writing and your religious practice? How do the two complement or build on each other?

FR: When you meditate in Soto Zen, you are not doing it to achieve something. You are not striving for enlightenment. Rather, the zazen that we practice is simply an expression of our original enlightenment, because we are all already enlightened. In other words, there is nothing to “get”. There is nothing to achieve. You sit zazen because that is what Buddhas do – Buddhas sit zazen.

For me, there’s a subtle twist to it that’s related to writing. When I sit down to write, of course I want to finish a book and then I want the book to be published, so there’s that kind of outcome. But I don’t focus on that when I’m writing. When I’m writing, I just write. There’s a part of my mind that understands that there’s this other project going on, the project of publishing, but I don’t focus on that – I focus on following the book as it’s being created. There’s a different kind of relationship.

Zen practice has helped me to let go of this result-orientation in writing. Part of it involves a kind of belief that when the book is finished, it will simply be an expression of my Dharma position or my understanding of the Dharma at a particular point in time, which will of course change. But that’s OK, because that is the Dharma expression.

DRW: When I was 19, I thought about becoming a Buddhist priest. I asked my teacher to let me be ordained, and he just smacked me on the head and said, “You don’t know what you’re talking about. Go away.” I went three more times when I was 20 and 21. The last time he said, “Do you even know what it means to become a Soto Zen Buddhist priest?” I knew that was a trick question, so I said, “No, I don’t know. Please tell me.” He said, “Being a Buddhist priest means you no longer have holidays, because when everyone else has holidays, that’s the busiest time in the temple. If a temple member is worried about their young child and wants to talk to you, you can’t say, ‘Well, it’s after five, I’m not going to talk to you.'” He said putting on a robe meant, “How can I help you?”

Our job as Buddhist priests is to alleviate suffering, not increase it. Could you talk more about the role of storytelling in alleviating suffering? That’s another way of describing what it means to do the work of a Buddhist priest and the work of a novelist.

There is nothing to “get”. There is nothing to achieve. You sit zazen because that is what Buddhas do – Buddhas sit zazen.

FR: The idea of writing a novel that helps and doesn’t hurt is something I take very seriously. When I write, I write first and foremost for myself. But at some point you have to think about publishing and be aware that this novel is going to go out into the world. How can it help people and not hurt them?

It’s true that when you put on a dressing gown, you don’t say no to people. You try to open your arms and be available, and that can be a challenge because the job of a novelist is very lonely. In order to write, I need to shut myself off and have loads of unstructured time to get deep into the novel. And that’s a conflict.

DRW: There is always a place for a deep mountain hermitage.

FR: That’s true, and that’s why I live on a remote island in British Columbia, in an area called Desolation Sound. But I also think of the Japanese tradition of hijirithe mountain ascetics and entertainers.

DRW: That’s right, the Hijiri go to the mountains and then come to the cities to do performing arts and tell stories.

FR: That’s me. (laughs) I go up the mountain, then I come down from the mountain and I’m the entertainer, and then I go back up the mountain. I was so relieved when I heard about Hijiri. I thought, “Yes! A historical precedent.”

This conversation took place on April 12, 2024, as part of the William Belden Noble Lecture at Harvard University’s Memorial Church. This excerpt has been edited for length and clarity.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(1259x575:1261x577)/ben-affleck-jennifer-lopez-4-2000-2952052960fb430eba246d8cd863ca0d.jpg)