I first visited Lebanon in 1978, three years after the civil war began and six years before Theodore Ell was born. I mention this because, despite the fact that we experienced this fascinating country at different times, his impressions and judgments in his excellent new book Lebanon Days – which covers the turbulent period from 2018 to 2021 – closely match my own.

The first time I travelled to Cairo, I was studying Arabic in Cairo on behalf of the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs. The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs (the acronym did not have a ‘T’ then) was looking to expand its Middle East expertise after Gulf oil producers caused oil prices to skyrocket following the 1973 Arab-Israeli war.

My department had approved the trip so that I could expand my knowledge of the Middle East and practice Arabic in a variety of environments where this devilishly difficult language is spoken. This was a three-week budget trip through Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan – using “service” taxis (taxis with multiple passengers) and staying in hotels that would barely earn half a star.

I wanted to be fully immersed in environments where little or no English is spoken and I needed to be able to communicate in Arabic on a daily basis.

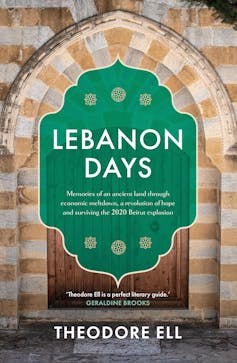

Book review: Lebanon Days by Theodore Ell (Atlantic)

Beirut: a divided city

Before flying to Beirut, I read books about the region in the embassy library in Cairo. The books about Lebanon date from before the civil war. I was impressed by the beauty of downtown Beirut, especially Martyrs’ Square (which appears several times in Ell’s book) with its large palm trees on its east and west sides.

At Beirut airport, just south of the city, I stopped a taxi and asked the driver in “Fus’ha” (formal) Arabic to take me to Martyrs’ Square. He looked at me in surprise – I assumed because my Arabic was not “Subscribe‘ (colloquial) dialect he was used to. But there was another reason. When we arrived at the square, all the palm trees had been cut off by high-velocity bullets about a meter above the ground.

I had stumbled upon the “green line” that separates Beirut’s east and west, the main battle zone of the war. The taxi driver was obviously nervous about being near the square and, as a Muslim, he did not want to take me to the Christian east.

In the years that followed, I visited Beirut several times during the war. In the late 1990s, when the country seemed to be getting back on its feet for a few years, I worked there for three years.

Jo Kassis/Pexels

While stationed in Damascus, the capital of Syria, in the mid-1980s, I would travel to Beirut with another staff member during lulls in the fighting to perform various official duties. When we stayed in West Beirut, we usually slept in the then-closed embassy building. As a precaution, we would drag mattresses from the bedrooms into the interior hallway to minimize the risk of being hit by broken glass in case an explosion occurred near the building.

Another vivid memory of this time is being invited by a Lebanese businessman to lunch at one of Beirut’s finest restaurants. The food was French and the interior was what you would expect from an upscale European restaurant. The only detraction from the delicious dining experience was that the restaurant’s windows were covered with sandbags.

The revolution of 2019

The Taif Agreement of October 1989 is generally regarded as the formal end of the war. But even then, René Moawad, the first Lebanese president after the war, was in office for only 18 days before he was assassinated by unknown assailants on November 22 of the same year.

Rafiq Hariri, who served as prime minister for six years in the 1990s, invested much of his personal wealth in rebuilding Beirut after the war. During this time, he encouraged other businessmen to voluntarily pay 10 percent of their income to the state to finance reconstruction.

I remember a business friend telling me that he thought this demand was a joke – nobody would pay such a tax. I asked him how he imagined the government would finance schools, hospitals and roads without taxes. He replied that in Australia I could reasonably assume that my tax payments would be used for these purposes. In Lebanon such payments would end up in Swiss banks.

In Lebanon Days, Ell tells many such stories, based on his experiences accompanying his wife Caitlin, an Australian diplomat, on a mission at our embassy in Beirut.

His term also saw the economic disaster caused by the devaluation of the Lebanese pound. The Lebanese Central Bank had kept the value of the pound artificially high from 1999 to 2019, at 1,507.5 to the US dollar. This distorted the economy by making imports artificially cheap and exports more expensive, hindering the development of export industries and leading to the accumulation of unsustainable deficits.

This policy was based on the central bank being able to obtain dollars cheaper than it was selling them in order to maintain the value of the pound. It was a confidence trick that was ultimately destined to fail, which happened in October 2019. The result was a social collapse – Subscribe or revolution, which led to months of unrest. Members of all 18 religious communities in Lebanon were equally affected, and protesters of all faiths gathered in Martyrs’ Square to shout slogans and sing protest songs. According to Ell, one of these slogans described Lebanon as “a nation of sheep led by wolves and owned by pigs.”

Andre Pain/AAP

Then, in early 2020, Covid hit the country: Ell and Caitlin included. But that couldn’t stop the revolution, which eventually culminated in another disaster – the horrific explosion at the port of Beirut in August 2020, which was caused by the negligent storage of a huge amount of ammonium nitrate.

Ell won the 2021 Calibre Essay Prize for his essay published in the Australian Book Review, which described the explosion and its impact on the city’s residents in vivid detail. He goes into more detail about these details in his book. I was particularly struck by his comment that the ammonium nitrate had not been moved to safer storage because no one had figured out how to make money off it.

Ell’s book brings reality to anyone who has lived in Lebanon. He vividly describes the Lebanese sense of fun, the nightclubs in East Beirut where patrons could drink and dance until dawn – even at the height of the civil war.

The flip side was the Lebanese’s determination to keep up appearances while the economy collapsed around them. Those who frequented fancy malls but ran out of money for more than basic necessities continued to walk the mall aisles – buying nothing but carrying a luxury brand shopping bag to pretend they had money.

The war that never ended

Right at the beginning of Lebanon Days, Ell points out that the civil war was not over: it simply became invisible. He describes it like this: “The religious differences in Lebanon have refined alienation into a way of life.”

Particularly revealing is his account of Genevieve, a Maronite Christian who “told us frankly, as if it could not be otherwise, that she had never met a Muslim.” Genevieve “spoke as if the number of Muslims in her country – in her entire region of the world – was not a historical fact, not a fixed fact of life, but something offensive and evil that must be opposed.”

To make the Taif Agreement work, a national unity government was formed in the early 1990s, made up of the various sectarian leaders who had fought the war. The main objector to this agreement was Samir Geagea, the leader of the Lebanese Forces, a Christian militia. Geagea opposed continued Syrian influence in the country’s government. In 1994, he was arrested and imprisoned for alleged crimes committed during the war. No such charges were brought against other ministers, although they could be accused of similar crimes.

Ahmad Omar/AAP

I remember that in 1997, the US ambassador invited a group of Lebanese politicians and some Western ambassadors to his residence to brief a US Congressional delegation on these post-war agreements.

A congressman asked if the Lebanese had convened a “truth and reconciliation commission” after the war, as South Africa had done after the abolition of apartheid. One of the guests was the mercurial Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, then a minister. He immediately replied, “No, in Lebanon we were more sophisticated. We put all the war criminals in the cabinet, and any war criminal who refused to become a minister was put in prison.” Amid laughter, the U.S. ambassador explained to the bewildered delegation that that was essentially what had happened.

Conspiracy theories

Ell builds his narrative chronologically, but adds a foreword explaining how Lebanon became the country it is today.

He describes the remarkable steles (stone slabs used as markers in ancient times) on the cliff face near the Dog River, north of Beirut. Each stele is dedicated to an invader – from Ramses II of Egypt, to the Romans, the Ottomans, the French under Napoleon III, and even a contingent of the Australian Imperial Force, whose plaque commemorates their campaign against Vichy French forces in Lebanon in 1941.

He describes the conspiracy theories that Lebanese espouse as a result of the constant threat of Israeli military action, which usually follows attacks on Israel by Hezbollah, the Shiite militia that is better armed than the Lebanese army and over which the government has no authority. Sonic booms from Israeli planes breaking the sound barrier over Beirut lead to an instinctive search for places to hide.

Doris Pemler/Flickr, CC BY-NC

Ell ends the book with a sad account of his and Caitlin’s departure. They had made many Lebanese friends, but many of them were leaving the country as well. The only ones who were somewhat happy to stay had dual citizenship, which gave them a foreign hiding place in case of another disaster.

The book is well designed. It includes a map of the places mentioned in the story, a useful historical timeline, a glossary of Arabic terms, and a guide to further reading.

Lebanon Days is a meditation on a country that never leaves its visitors unmoved. Ell is a gifted writer: his prose is unaffected, precise and elegant. He has used the drama of his three years in Lebanon to shed light on the past of this fascinating country – and to point to a future that looks bleak at the moment, especially given the ever-present threat of war between Israel and Hezbollah. But what also comes through is the resilience of its people. This paradoxical country has elevated survival to an art form.