Noah Lyles and his longtime sports psychologist, Diana McNab, have been running a pre-race program all season long. Together, they’ve created a script of sorts that lays out the psychological game plan for race day – what Lyles should be thinking when he wakes up, when he arrives at the track, when he warms up, when he’s in the starting blocks, and so on. This mental script is designed to produce strong physical results.

As usual, McNab spoke to Lyles on the phone the night before his 100-meter race in Paris and rang her Zen bells three times while Lyles did breathing exercises before visualizing each element of the script.

“It always sounds like Zen!” says McNab.

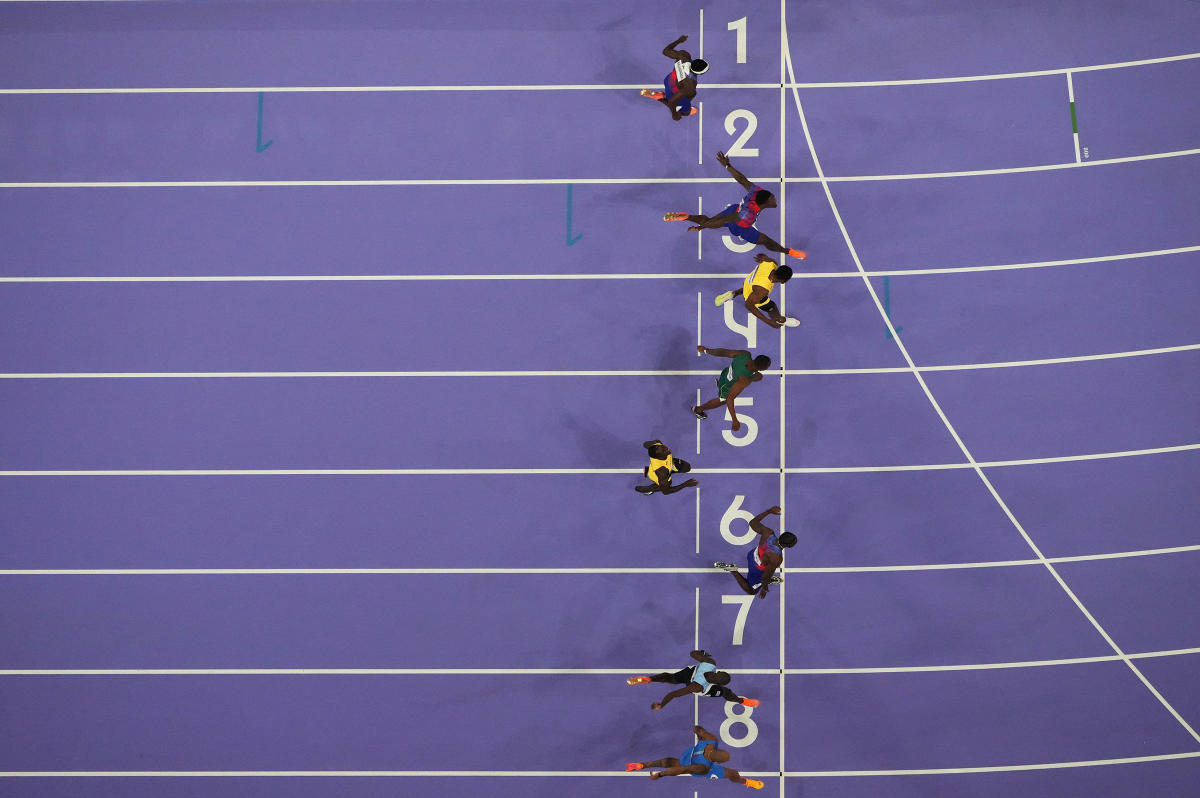

The plan worked on Sunday night when Lyles won the most incredible, dramatic and competitive 100-meter final in Olympic history. In a photo finish at the Stade de France on Sunday night, Lyles beat Kishane Thompson of Jamaica by five thousandths of a second.

When Lyles woke up on Sunday, his first step was to “imagine he was 12- to 15-year-old Noah – laughing, funny, fearless,” according to the script McNabb shared with TIME after the race. By the end of his warm-up, he was supposed to be as loose as a “Raggedy Ann doll.” As he entered the track, he had to “look around and take in the thousands of spectators and the energy in the stadium” – something he couldn’t do in Tokyo, where there were no fans and Lyles went home with a disappointing bronze medal in the 200m. In the final 20 meters, he was supposed to “fly down the track. Nobody can stop me. I’m on fire. I have a God-given extra gear.”

And when he crosses the finish line, the script says, he will set his personal best time, finish first, smile and feel a sense of relief.

Check, check, check, check. All that was really missing was the agonising wait for Lyles, Thompson and bronze medallist Fred Kerley while the judges decided the photo finish. Then he could let out a giggle on the track, do his victory lap and officially back up the cheeky words he’d been saying all year: the 100m was now his.

Lyles finished second in his semifinal heat on Sunday behind Jamaica’s Oblique Seville. Was Lyles not fast enough that night or was he just conserving energy? “I told him to try and win,” said Lyles’ trainer Lance Brauman. “To be honest, I thought Oblique ran an incredibly good race.”

Even Lyles’ mother, Keisha, was a little nervous in the stands at the Stade de France. Seville and Thompson, who had already run the fastest time of the year before the Olympics, looked impressive. She called Lyles’ agent and shared her honest observation with him.

“This finale,” said Keisha, “is going to be a bitch.”

Between the semifinals and the final, Brauman challenged Lyles to run more aggressively between 30 and 50 meters. He told him that the next time he saw Lyles, he would see the Olympic 100-meter champion in front of him. Brauman told his protégé that the showman would appear at the big moment. McNab and Lyles also spoke: she told him to relax and stop carrying tension in his body.

During his introduction for the final, Lyles did a triple jump — plus two or three more jumps — about a quarter of the way down the track. He was the only finalist to do so: his takeoff was not muffled at all. Does Brauman worry that Lyles’ showmanship will drain his energy or put him at risk of injury?

“To be completely honest, I try not to watch,” Brauman says. “He does what he does. If I got involved in that, I’d be a nervous wreck the whole time.”

Read more: Noah Lyles brings his speed and enthusiasm to the Olympic Games

Lyles’ reaction time at the start – 0.178 seconds – was the worst of the race. “Damn, I’m unbelievable,” Lyles said afterward. “This is crazy. I thought I was a little better, but this proves you don’t win races with reaction time.” While Thompson was three lanes away, Seville was running to Lyles’ left, in his peripheral vision. “I was very lucky to have Oblique Seville right next to me,” Lyles said. “Because I felt all year that he had achieved the acceleration that I hadn’t achieved. So I figured the fact that he’s here means I’m not going to let him go.” Seville finished in last place.

As Lyles reached his top speed, Brauman — who was sitting on the backstretch near the finish and didn’t have a good view of the start — found new hope. “I felt really good when I saw where he was at 60,” Brauman said. “OK, we’re in.” Lyles leaned back at the finish, which he really shouldn’t do because it causes the slightest bit of delay that can cost a sprinter dearly. “I thought I leaned back too early,” Lyles said. But he got away with it. Barely. Like, really, really close.

As the runners and 80,000 fans at the Stade de France stared at the scoreboard wondering who had won, Lyles walked up to Thompson and told him he thought the title was his. “Brother, I think you have the one big dog,” Lyles told him. “And then my name popped up. And I just thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m amazing.'”

NBC held a microphone out to Keisha, and she screamed so loudly that a producer told her to turn down the volume on her headphones.

Read more: 6 athletics rivalries to watch at the Paris Olympics

The times shown on the scoreboard – 9.79 seconds – were the same for Lyles and Thompson. So why wasn’t the race a tie? It turned out that Lyles won his gold medal in 9.784 seconds. Thompson took his silver medal in 9.789 seconds. American Fred Kerley took bronze in 9.81 seconds.

Lyles is guaranteed a win in the 100m, 200m and the 4x100m relay. Usain Bolt has achieved this feat at three consecutive Games in Beijing, London and Rio. Lyles promises less drama in the 200m, where he is the reigning three-time world champion, on Thursday night.

“When I come out of the corner,” Lyles said Sunday, “his opponents will be depressed.”

Maybe they should try some Zen chimes.

Write to Sean Gregory at [email protected].