If you traveled this summer, the price you paid at hotels may have been artificially inflated. According to two lawsuits, numerous hotel operators are participating in an illegal scheme to increase their prices.

In a traditional price-fixing scheme, rival managers meet in a smoke-filled room to manipulate prices. In the modern version, competitors don’t have to talk to each other. Instead, companies that would normally compete send their internal data to a third party. That third party then uses an algorithm to recommend the companies the “optimal” prices for their customers.

Even if the mechanism is different, the result is the same: customers pay significantly higher prices than they would in a truly competitive market.

A lawsuit filed last year accuses many Atlantic City casino hotels, including Caesars, Harrah’s, Tropicana, Borgata and Hard Rock, of “engaging in an ongoing conspiracy to set, increase and stabilize room prices.” Together, these hotels control about three-quarters of Atlantic City’s rooms. According to the lawsuit, the casino hotels conspire by using a “common pricing algorithm platform” called Cendyn.

The casino hotels provide the platform with “continuously updated, non-public room rate and occupancy data.” Cendyn then “uses this information to generate ‘optimal’ room rates, updated multiple times a day, that each client can charge to their guests.” The product, previously known as Rainmaker, is designed to “solve” the problem of “competitor price shopping.”

According to Cendyn, its customers accept the “optimal” price suggested by the Cendyn algorithm 90% of the time. The company advises its customers that accepting the recommended prices will result in an increase in revenue of “up to 15%.” Since 2018, when Atlantic City hotel-casinos began using Cendyn, there have been “significant increases in room rates and revenue, along with significant decreases in occupancy rates.”

Traditionally, Atlantic City hotel-casinos competed on price to increase occupancy. Hotels charging higher prices were undercut by competitors offering similar rooms at lower prices.

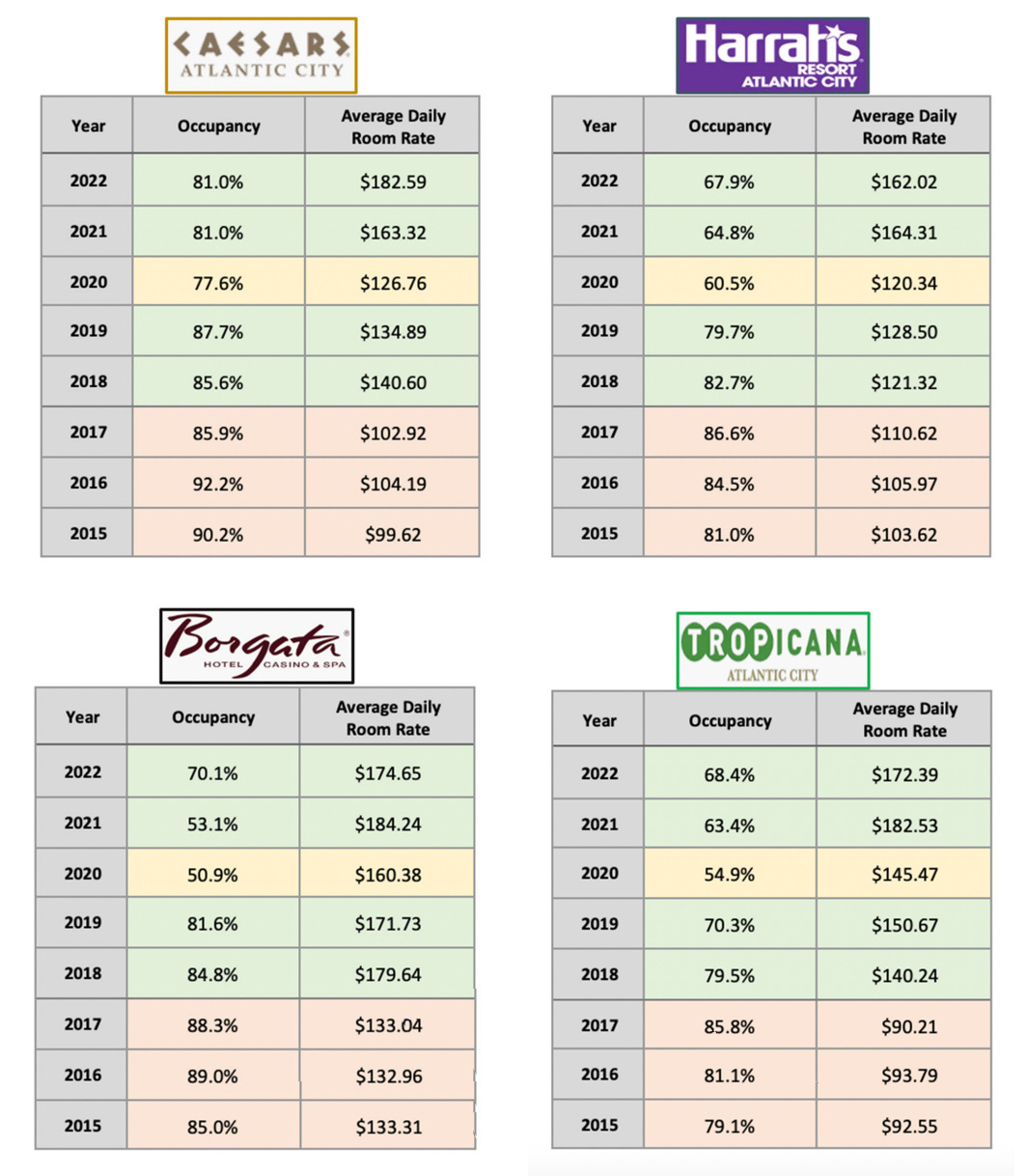

When hotel-casinos began using the Cendyn to set their rates in 2018, that changed. Records filed with New Jersey state authorities show that all hotels significantly increased their rates and caused occupancy rates to drop. (The year 2020 is highlighted in yellow because travel was significantly restricted due to the pandemic.)

That strategy worked, leading to an overall increase in Atlantic City’s “room revenue” – from $495 million in 2017 to $698 million in 2022, according to state records. During the same period, the average room rate rose from $108 per night to $188 per night and occupancy rates fell from 87% to 73%.

The strategy worked because all hotel-casinos followed this strategy at the same time. Some potential guests were scared away by the prices, which reduced occupancy. But the casino hotels were able to increase their overall revenue because everyone who wanted to stay in Atlantic City was practically forced to pay the higher price. There were no alternatives.

The defendant hotel-casinos argue that the use of Cendyn does not violate antitrust law because there was no direct communication between competitors and the prices recommended by Cendyn were not binding. They are asking a federal judge to dismiss the lawsuit.

The Justice Department’s Antitrust Division filed a “statement of interest” asking the court to reject that argument. In the brief, the Justice Department argues that price-fixing agreements do not require direct communication between the parties involved. The Sherman Antitrust Act, the Justice Department says, “prohibits competitors from delegating important aspects of pricing decisions to a common entity, even if the competitors never communicate directly with each other.” The Justice Department also says it does not matter that the prices Cendyn recommended were not binding. A collusion “to establish the starting point of prices is … unlawful, regardless of what prices competitors ultimately charge.”

If that sounds similar to the alleged use of RealPage software by commercial landlords to increase rents, that’s no coincidence. Both Cendyn and RealPage software are made by the same company: Rainmaker.

Rainmaker sold its “property management and data analytics software” to RealPage in 2017 to “focus exclusively on the hotel and gaming industries.” In August 2019, Rainmaker sold its remaining hotel and casino software business to Cendyn for an undisclosed sum.

Federal authorities raid commercial landlords and intensify nationwide investigations into rent increases

The allegations that hotels are conspiring to inflate room rates extend well beyond Atlantic City. In a class action lawsuit filed earlier this year, plaintiffs claim that luxury hotels in major cities across the country are conspiring to raise their prices using a software program called Smith Travel Research (STR), which is owned by CoStar.

The lawsuit involves many of the country’s most prominent luxury hotel brands (Hilton, Hyatt, Intercontinental and Marriott) operating in 15 major cities (Austin, Boston, Chicago, Denver, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Miami, Nashville, New York, Phoenix, Portland, San Diego, San Francisco, Washington DC and Seattle). According to the lawsuit, these luxury hotels “agreed to share their detailed, verified, competitively relevant information about their rates, offerings and future plans” on an ongoing basis through STR. This allows the hotels to “set higher prices than they would have without this information-sharing agreement.”

Under the agreements signed by luxury hotels with STR, they can only obtain their competitors’ pricing and delivery information if they also provide the same information to STR. While STR does not provide exact price recommendations, it uses the data to inform hotels whether their prices are high enough to receive their “fair share” of revenue.

According to a whistleblower who provided information to the plaintiffs in the case, STR is used by nearly every luxury hotel in the country. “STR is like oxygen or water to the hotel industry. You just have to have it,” said a confidential witness. Like Cendyn, the data STR provides to luxury hotels “enables and encourages them to increase room rates even at the expense of occupancy because they are informed of their competitors’ past actions and planned strategies.”

The luxury hotels want to dismiss the lawsuit because they only use STR for “benchmarking” and have not violated any antitrust laws. They describe the plaintiffs’ arguments in the lawsuit as “fanciful.” The case is still pending.