The term “stylist” is full of mystery and allure, a concept that has sparked endless debates among writers and readers. Despite its charm, it carries a heavy burden. For those who dare to write or feel attracted by its allure, it can cause serious psychological problems: burnout, inferiority complexes and even deep depression.

In 1925, F. Scott Fitzgerald achieved literary greatness with The Great Gatsby. His language, his storytelling, were captivating and propelled him to international fame. But the very style that took him to such dizzying heights soon became a double-edged sword. When he tried to recapture the same magic in later works, he failed. The brilliance that once burned so brightly began to fade, and he struggled with a sense of failure and financial despair. Fitzgerald’s story is a haunting reminder of how the very style that can lift a writer to heavenly heights can just as easily plunge him into the abyss – a narrative that is as poetic as it is unsettling.

Philologists who study the nature of language insist that concepts that shape our lives must be precisely defined. For them, every dramatic event is anchored in a concept, and even if such a concept does not yet exist, it must be born into language. The goal is to illuminate our understanding and to see events as clearly and precisely as possible. But this raises a huge question: who then has the authority to define “style”? Or, more precisely, who can determine who is truly a “stylist”?

The answer is simple: a voracious reader. But not every reader is suitable – that reader must possess a refined palate and a wealth of knowledge. Imagine a reader who has devoured thousands of books, who is well versed in literary history, who understands the nuances of aesthetics. How rare are such people! The term “stylist” is a fragile, delicate matter – so much so that even its definition requires a person of exceptional judgment. It is this discerning reader who has the power to grant a writer immortality.

But this almost mystical concept is not just limited to the world of literature. It also permeates the world of music, where it proves to be an unforgiving benchmark. Composers, virtuosos, conductors – they have all been tested by this unforgiving concept, creating an atmosphere of fear that could have come straight out of a Tim Burton film, where the shadows are long and the sense of dread is palpable. Artists desperate to carve out their place in history are known to shudder at the mere thought of it. The whole ordeal is nothing short of scary.

And yet there are people who escape this stranglehold. Joaquín Rodrigo, for example, composed the “Concierto de Aranjuez” in 1939 at the age of 38, breaking the icy grip of stylistic expectations and establishing himself as a force to be reckoned with. Maurice Ravel made a similar breakthrough when he introduced the world of ballet to “Boléro” and secured a place for himself as a “stylized artist” in the eyes of the authorities. Richard Wagner only achieved such recognition after the monumental creation of the “Ring Cycle,” his epic magnum opus of four operas.

But not everyone comes out unscathed. Franz Schubert, who died at the tender age of 31, was a man tormented by the curse of “style.” Although he is now revered as one of the greats of his time, Schubert spent his final days in a relentless cycle of self-doubt, mercilessly questioning his worth as an artist.

His reflections on this struggle are engraved in his works, especially in the sad sounds of “Winterreise”, in which the echoes of his inner unrest still resonate.

Signature of the Spirit

In this context, it is clear that style is far more than just a superficial embellishment in writing or composing. Rather, it is the very essence of how we articulate our thoughts and connect with the world around us. Style is deeply woven into the structure of our expression, shaping the way we convey ideas, emotions, and perspectives. Every writer, composer, or orator leaves a distinctive stylistic fingerprint—a blend of syntax, diction, tone, and rhythm that sets their work apart from others. This uniqueness is not just a matter of taste; it is an outward manifestation of their innermost worldview, akin to a signature imprinted on each of their works. Style goes beyond mere technique. Georges-Louis Leclerc, known as the Count of Buffon, famously summed up this idea in his epigram from Discourse on Style, in which he asserted, “Le style est l’homme même” (“Style is man himself”). Similarly, Arthur Schopenhauer compared style to the “physiognomy of the mind” and believed that it reveals the true nature of a person’s intellect and spirit.

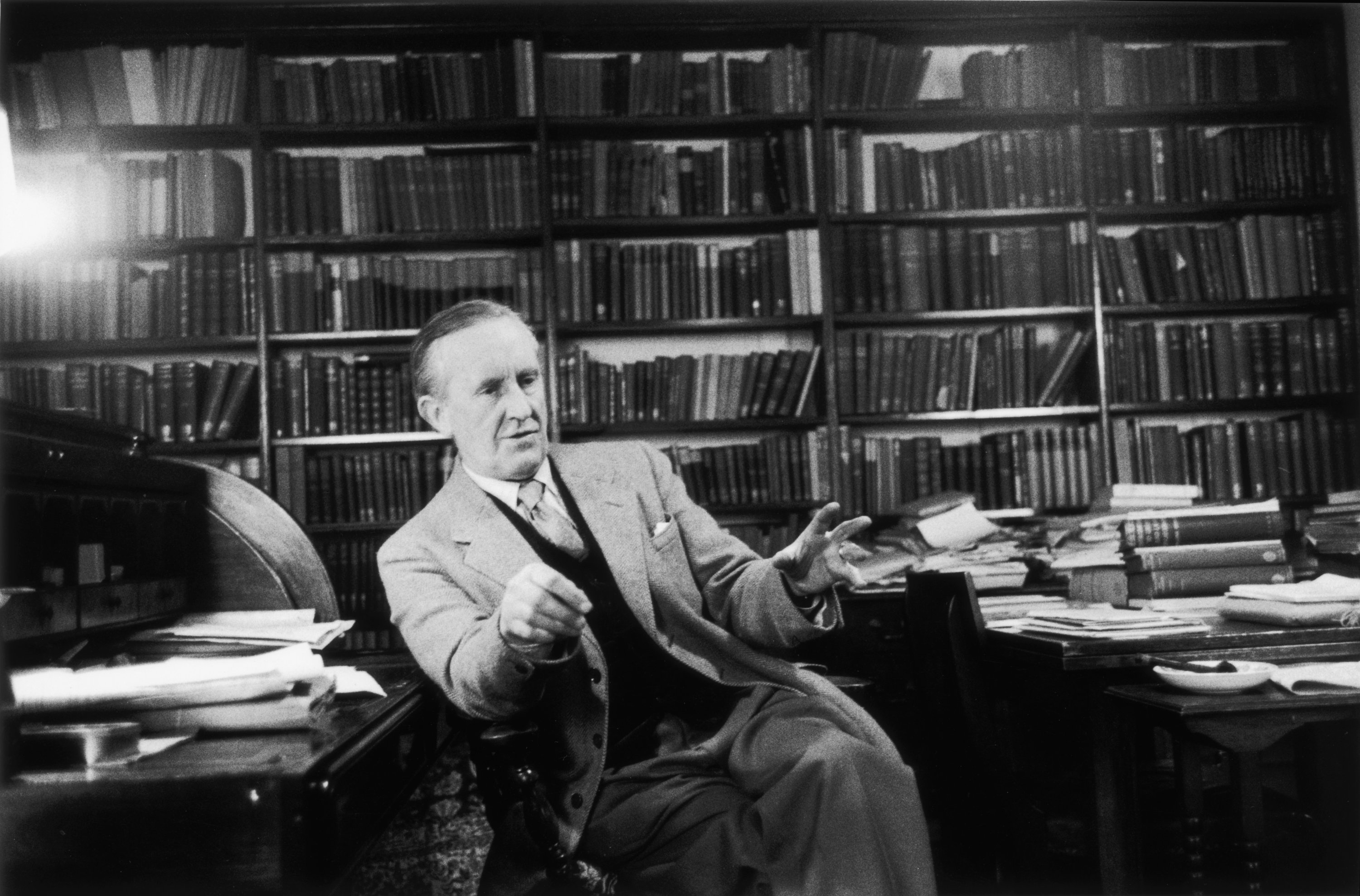

Think of literary greats Thomas Mann and JRR Tolkien. Mann’s prose, a labyrinth of philosophical questions and self-examination, reflects his own thoughtful and inquiring mind. His words are not just sentences; they are pathways into the depths of human existence, each carefully constructed to guide the reader through complex ideas and emotions.

Tolkien, on the other hand, creates a sprawling universe filled with elves, orcs, and epic adventures. His style is a direct reflection of his boundless creativity and his deep love of mythology and language. Through their unique styles, both Mann and Tolkien offer readers a window into their souls.

History in brief

Stylistics is a journey through time, deeply rooted in the thought of the Greeks. It all began with Aristotle’s Rhetoric, a work that laid the foundation for persuasive style by dissecting ethos, pathos and logos – the trinity of rhetoric that still influences how we influence our minds and hearts today. In ancient times, rhetoric was not just a tool; it was an art, a powerful force that could shape societies by directing public opinion and thought.

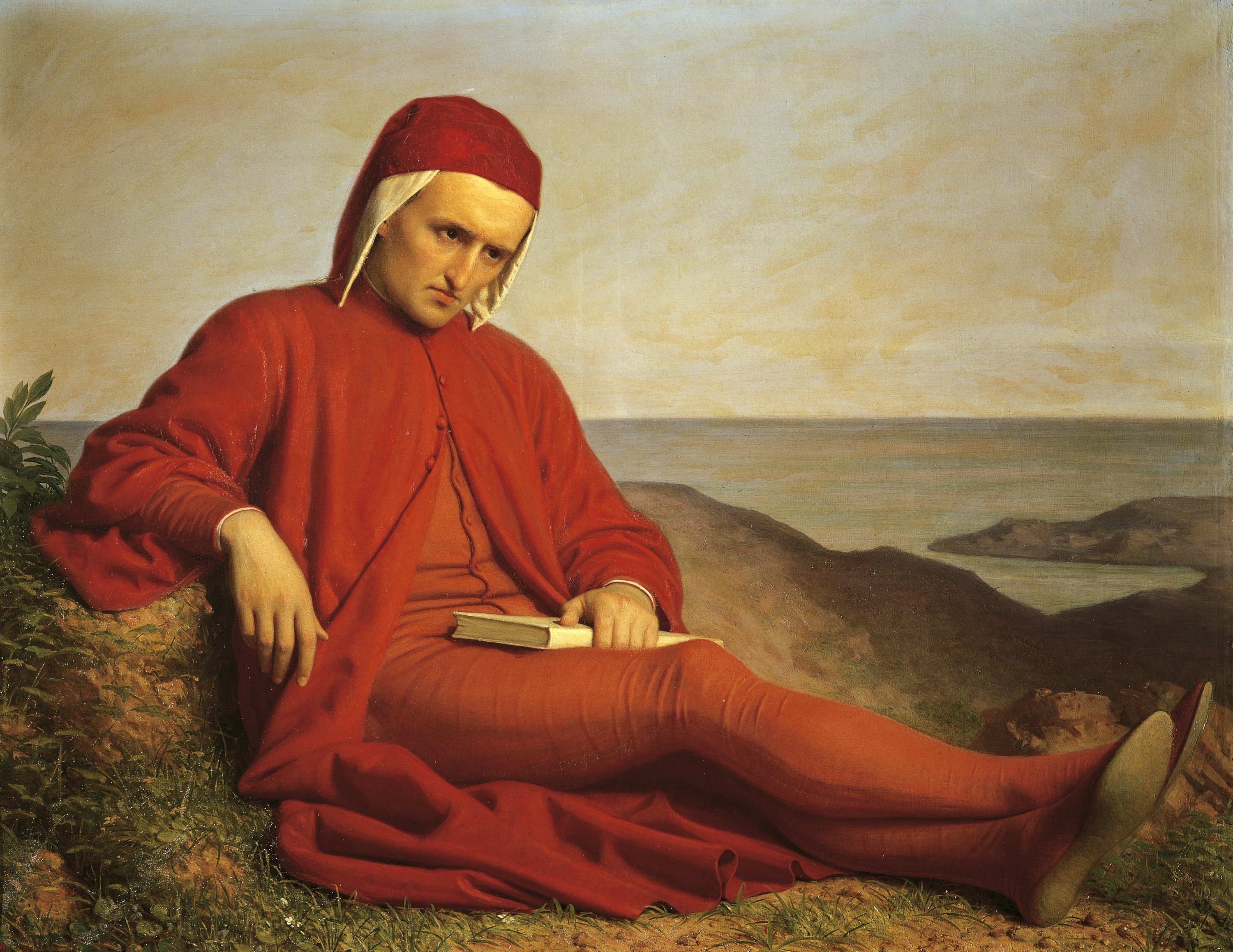

As the world entered the Middle Ages, stylistics became a bridge between theology and philosophy. The power of style was used by thinkers such as Dante Alighieri, who in the verses of the Divine Comedy not only told a story but also wove together spiritual and philosophical ideas.

The Renaissance, with its revival of classical ideals, brought stylistics into the realm of the individual. Figures such as Erasmus represented a style that was clear, elegant, and reflective of personal expression. This era marked a departure from the collective voice of the Middle Ages and instead celebrated the unique perspective of the individual. Style became a mirror of the self.

With the Enlightenment, the focus shifted again, this time to clarity, reason, and precision of thought. In this age of reason, style was examined for its ability to convey ideas with precision and logic. Writers such as Voltaire and Jonathan Swift embodied this approach, engaging in the social and political debates of their time with their sharp, clear prose.

But as the world entered the Romantic era, style changed again, this time with the aim of embracing the power of emotion and the inner world of the individual. Writers such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Lord Byron broke with the rigid structures of Enlightenment clarity and instead used style to explore and express the depths of personal feelings. Romanticism celebrated the subjective, the passionate, and the unique. Style became a conduit for the raw.

The 20th century brought a new wave of change as stylistics and literary theory merged. The rise of structuralism and post-structuralism challenged traditional notions of style, viewing it not just as a means of expression but as a force that shapes meaning itself. Scholars such as Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault examined how stylistic choices affect the perception of texts and how they construct the reality around us. In this era, style was dissected, analyzed, and reconceptualized as a dynamic component of meaning-making that interacts with the reader’s mind to create layers of interpretation.

Sonnet and Tweet

Today, stylistics is a multidisciplinary field that combines literary analysis with linguistics and psychology. It studies how style influences meaning, identity and communication across different media. The digital age, with its emojis, memes and internet slang, has brought entirely new dimensions to stylistic expression, reflecting the rapidly evolving ways we communicate in a connected world. Today, stylistics is not just about literature; it is about understanding the nuances of communication in all its forms, from the Shakespearean sonnet to the tweet.

Having woven through the tangled threads of style, we arrive at a truth as sharp as Occam’s razor: style, that esoteric chameleon, is nothing more than a mirror. A mirror that, when polished, reflects the soul of the creator – but when shattered, it turns into a hall of illusions, distorting any attempt to recapture the lost magic. The pursuit of style is a thrilling, nerve-racking game of Russian roulette, where each turn of the chamber can lead to literary immortality – or to silent disappearance into oblivion.

In the end, the ultimate style may not lie in the pen and the bravura of expression, but in the quiet confidence of leaving the stage before the curtain falls. After all, not every play ends with applause; some stories are meant to hang in the air unresolved, like an unfinished symphony.