The news cycle moves so fast that it can seem impossible to take it all in. We are overwhelmed, exhausted and sometimes helpless. Hollywood-based nun, artist and teacher Sister Mary Corita (aka Corita Kent) understood this. She lived and worked in the 1960s, also a time of tremendous political change and drastic historical events. She used her art and ideas to make sense of them. As she told a group of students in 1967, “Sometimes you can take in the whole world, and sometimes you only need a little piece of it. I think that’s what a work of art really is: it’s a little piece that you can take in that gives you an idea of the fullness of the whole.”

Sister Corita’s art reflected the idea of the small and the big picture. Working in screen printing, a medium that is widely accessible and available and can be produced in large quantities, she created text-based works in bright, bold colors. She often began her works with a recognizable phrase or slogan, framed by smaller, almost illegible text that invited the viewer to look more closely at the comments she inserted.

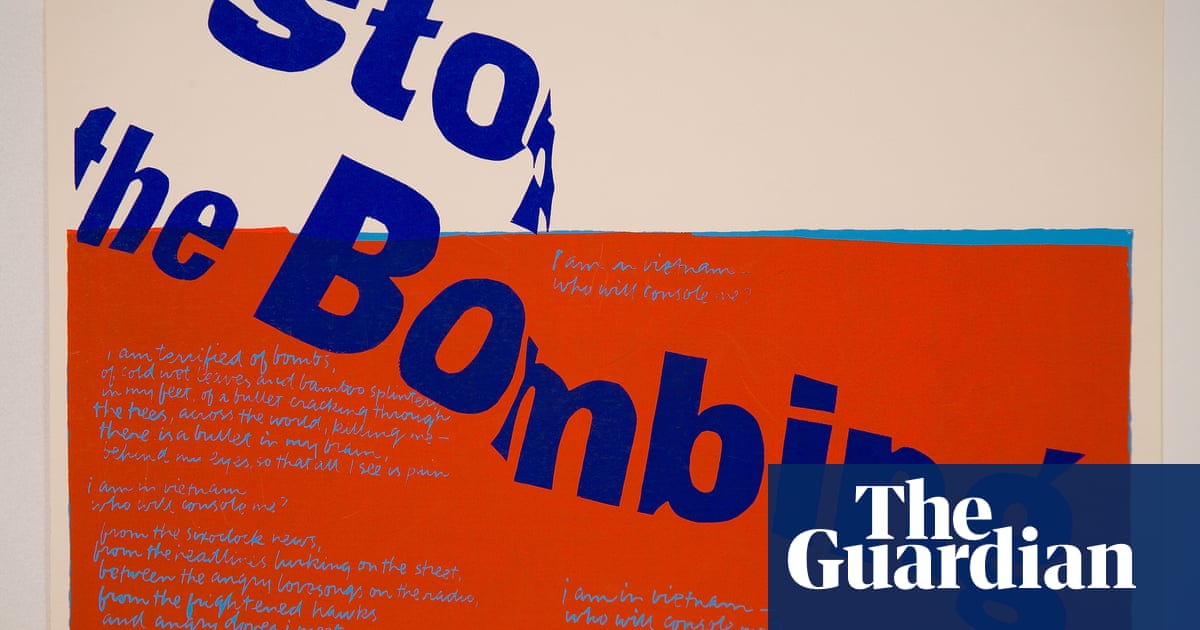

One of her most striking examples is Stop the Bombing, a 1967 print in red, blue and white (perhaps a reference to the US flag) protesting the brutality and violence of the Vietnam War. In the handwriting around it is a moving statement: “There is a bullet in my brain, behind my eyes, so all I see is pain. I am in Vietnam…” This message is prescient today. But only when we look closer do we understand the reality of these larger slogans – a lesson in looking beyond what is initially presented to us.

She also understood media manipulation, drawing attention to headlines that treated communities unfairly. During the Watts Uprising in LA in August 1965, she created My People, which turned the front page of the Los Angeles Times – which contained hateful language toward the black community – on its side and paired it with a red block bearing handwritten lines that flipped the narrative. In white embossing, this included a powerful sermon by Maurice Ouellet, a priest and civil rights activist who marched in Selma, Alabama, challenging “comfortable” bourgeois Christianity and the foundations of the faith.

This piece came to mind when I saw the headlines that may have contributed to the recent unrest in the UK, and how newspapers today still prioritise and spread narratives that suit their own interests. This is a powerful example of how art can be used as a tool to show us a different side of history and make us look more critically at what the bigger stories are telling us. Sister Corita dedicated her life to spreading messages of hope, faith and justice – and, just like artists Barbara Kruger and the Guerrilla Girls, used recognizable graphics, logos and symbols to incorporate the world into her art and make it relevant to all.

Her teaching methods also involved looking closely at the world. When she was head of the art department of her order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, she encouraged her students to use a viewfinder—a piece of paper or cardboard with a square hole in it that they held up to see the smaller image in the middle of the larger image outside the frame.

Sister Corita died in 1986, but her legacy is great. Since 1997, the Corita Art Center has existed as an affiliate of the Immaculate Heart Community to preserve, promote and support her work and teaching methods. When I visited last year, I was inspired by her van (the “Corita Mobile”), decorated with her bright, bold artwork and driven by staff who bring art supplies to underserved neighborhoods to encourage people to make crafts and draw. Armed with her spirit, they spread her important messages, which are more relevant today than ever before.

after newsletter campaign

If she were to hold her viewfinder up to the modern world, what would she see? Sometimes zooming in on something small can show us the reality of an individual’s experience, but it can also reveal the beauty of the world – and remind us that hope is never lost.