You might think you know everything about Leonardo da Vinci. He painted the Mona-LisaAs an inventor, he developed flying machines centuries before the Wright brothers. And in 2017, a painting attributed to him fetched the highest price of any work of art at auction.

But did you know that he also researched and experimented extensively with scents? The exhibition “Leonardo da Vinci and the Scents of the Renaissance”, which is now opening at the Château du Clos Lucé in Amboise, central France, examines this fascinating and little-known aspect of the polymath’s work.

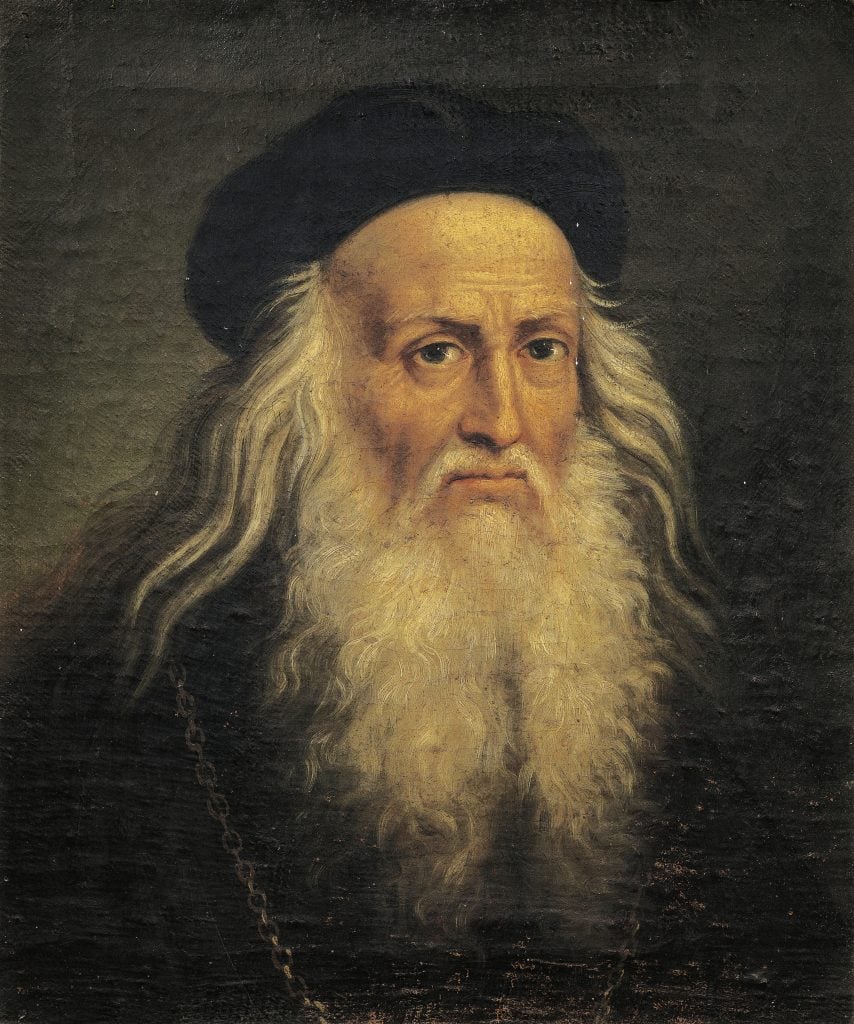

Portrait of Leonardo da Vinci, by Lattanzio Querena. Padua, Museum of Medieval and Modern Art. Photo: DeAgostini/Getty Images.

Leonardo came to Amboise at the invitation of Francis I, who reigned as King of France from 1515 to 1547. After hearing of the Italian’s diverse talents, Francis I appointed him “first painter, engineer and architect to the king.” In return for his services, he housed Leonardo at Clos Lucé, just a short walk from one of his own castles, the Château d’Amboise. Fatefully, it was at Clos Lucé that Leonardo wrote his will, handed over his notebooks and sketches to his student Francesco Melzi, and died in 1519.

The exhibition, billed as a multisensory, olfactory experience, reveals that Leonardo became interested in perfumes after comparing the effects of the sense of smell with those of sight and hearing. He collected commercially available perfumes, many made from oils, flowers and animal and vegetable fats, and recorded their recipes. He took notes on distillation and maceration techniques: “Remove the yellow layer that covers the oranges and distill them in an alembic,” he wrote in Codex Forster“until one can say that the distillation is perfect.”

A 16th century censer. Blois Cathedral © Léonard de Serres.

During the Renaissance, perfumes were often placed in censers similar to those used for incense. Thus, the perfumes also served as air fresheners, masking the ever-present smell of unpleasant odors. Leonardo designed some of these objects. Perfumes were also used to protect against diseases, which were believed at the time to be spread through miasma, or foul, polluted air.

One of Leonardo’s designs for a burning device was modelled on a bird that was Cyphre’s owlThe exhibition features a modern reconstruction displayed alongside the artist’s writings. Visitors can also smell the black amber necklace worn by the woman depicted in his 1489 painting. Lady with an Erminewhich gives off a sweet, earthy smell.

Gloves from the late 16th-early 17th century. Bargello National Museum, Florence © Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Firenze.

Other objects on display delve deeper into the world of Renaissance fragrances: cookbooks shed light on the art of perfume making in the 15th century; the fashion of the era is characterized by a splendor that matches the perfumes worn by their wearers; and portraits of Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio complete the picture of Renaissance opulence.

Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli, Santa Maria Maddalena. Municipal Museums of the Visconti Castle, Pavia © Musei Civici del Castello Visconteo, Pavia.

Leonardo’s interest in perfumes may have been sparked by his mother Caterina, a mysterious woman who may have been a freed slave brought to Italy from her home in the Caucasus via Constantinople. (This is still unknown after years of fruitless research.) Carlo Vecce, a professor of Italian literature at the University of Naples and one of the lead curators of the exhibition, documented her journey west in his research.

Installation view of “Leonardo da Vinci and the Perfumes of the Renaissance”. © Château du Clos Lucé – Parc Leonardo da Vinci. Photo: Leonard de Serres.

The exhibition takes visitors through themed rooms that highlight the diverse perfume cultures Leonardo’s mother would have encountered on the way to Italy. These range from the markets of Constantinople, where perfumes were used for purposes as diverse as healing, diet and religious worship, to the shops of the Spezieri, an order of medicine and spice merchants based in Venice. In both places, Caterina encountered scents from spices such as pepper, myrrh, hyssop and cinnamon.

Saint Mary Magdalene kneelingMusée de Cluny, Paris © GrandPalaisRmn (musée de Cluny – musée national du Moyen-Âge) / Image GrandPalaisRmn

Caterina came to Italy via a well-established trade route between the Byzantine Empire and the Italian city-states. Her arrival coincided with the introduction of perfumes, which were used in Asia long before they were widely used in Europe.

Although it may seem that the creation of perfumes is completely separate from Leonardo’s work as a painter, there is one commonality: we don’t know if Leonardo actually wore any of the perfumes he made. We do know, however, that one of his students favored a mixture of egg yolk, linseed, and rosemary oil, which he and his master made using the same techniques they used to mix paints.

“Leonardo da Vinci and the Perfumes of the Renaissance” can be seen until September 15 at the Château du Clos Lucé in Amboise, France.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay up to date in the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter and receive breaking news, insightful interviews and astute critical views that drive the discussion forward.