by Jordan Frith, Clemson University

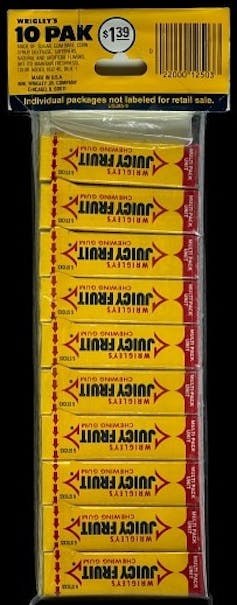

The first modern barcode was scanned 50 years ago this summer – on a 10-pack of gum in a grocery store in Troy, Ohio.

It’s 50 years old for most technologies, but barcodes are still very popular. Over 10 billion barcodes are scanned every day around the world. And newer types of barcode symbols, such as QR codes, have created even more uses for the technology.

I would have been like most people and never given the humble barcode a second thought if my research as a media studies major at Clemson University hadn’t taken a few strange turns. Instead, I spent a year of my life digging through archives and old newspaper articles to learn more about the origins of the barcode – and ended up writing a book about the cultural history of the barcode.

Although the barcode did not herald the end of times, as conspiracy theorists once feared, it did usher in a new era of global trade.

Barcodes were an invention of the food industry

While the world has changed a lot since the mid-1970s, the Universal Product Code (UPC) – what most people think of when they hear the word “barcode” – has not. First scanned on a pack of gum on June 26, 1974, the code is essentially identical to the billions of barcodes scanned in stores around the world today.

The Smithsonian Institution owns the first pack of gum with a scanned UPC code. Clyde L. Dawson/National Museum of American History

When that first UPC code was scanned, it was the culmination of years of planning by the U.S. grocery industry. In the late 1960s, labor costs in grocery stores were rising rapidly and inventory tracking was becoming increasingly difficult. Grocery store executives hoped the barcode could help them solve both problems, and they were ultimately right.

In the early 1970s, the industry formed a committee that developed the UPC data standard and selected the IBM bar code symbol over half a dozen alternative designs. Both the data standard and the IBM bar code symbol are still in use today.

From meeting notes I found in the Goldberg Archives at Stony Brook University, it appears that the designers of the UPC system believed they were doing important work, but they had no idea they were creating something that would long outlive most of them.

Even the most optimistic estimates from the food industry were that fewer than 10,000 businesses would ever use barcodes. For this reason, the scanning of the first UPC barcode received little attention at the time.

Some newspapers published short articles about the launch event, but they didn’t exactly make the front page. The importance of this action only became clear years later, when barcodes became one of the most successful digital data infrastructures of all time.

Barcodes caused a shelf revolution

Barcodes not only changed the shopping experience at the checkout, but by making products machine-readable, they also enabled huge improvements in inventory tracking. This meant that items that were selling well could be quickly restocked when the data indicated so, requiring less shelf space for each individual product.

As barcode expert Stephen A. Brown has written, the reduced need for shelf space allowed for rapid proliferation of new products. You can blame barcodes for your grocery store selling 15 varieties of barely distinguishable toothpaste.

Likewise, today’s giant grocery stores and supermarkets probably couldn’t exist without the massive amounts of inventory data that barcode systems generate. As MIT professor Sanjay Sharma put it, “If barcodes hadn’t been invented, the entire layout and architecture of retail would look different.”

Other industries quickly jumped on the bandwagon

The modern barcode was invented in the grocery industry, but it didn’t stay confined to supermarket shelves for long. In the mid-1980s, the success of the UPC system encouraged other industries to adopt barcodes. For example, within three years, Walmart, the Department of Defense, and the U.S. automotive industry began using barcodes to track objects in supply chains.

Private shipping companies also used barcodes to record identification data. FedEx and UPS even developed their own barcode symbols.

As sociologist Nigel Thrift explained, barcodes were “a crucial element in the history of the new world order” in the late 1990s, enabling rapid globalization in ways that would be hard to imagine without barcodes.

Black and white and unnoticed everywhere

As someone who was so interested in this history that I had the International Standard Book Number barcode of my latest book tattooed on my arm, the quiet farewell to the 50th anniversary of the barcode seems almost poetic.

I grew up in a world where barcodes were everywhere. They were on every product I bought, on the concert tickets I scanned, on the packages I received.

Like most people, I hadn’t given them much thought despite their ubiquity – or perhaps because of it. It wasn’t until I began researching my book that I realized how a barcode on a packet of chewing gum set off a chain of events that changed the world.

Stevie Edwards

For decades, barcodes have been a workhorse operating in the background of our lives. Modern humans scan them countless times a day, but we hardly think about them because they are inconspicuous and just work – at least most of the time.

Even though barcodes are long out of date, they remind us that these seemingly boring technologies are often much more interesting and important than most people realize.

Jordan Frith, Pearce Professor of Professional Communication, Clemson University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.