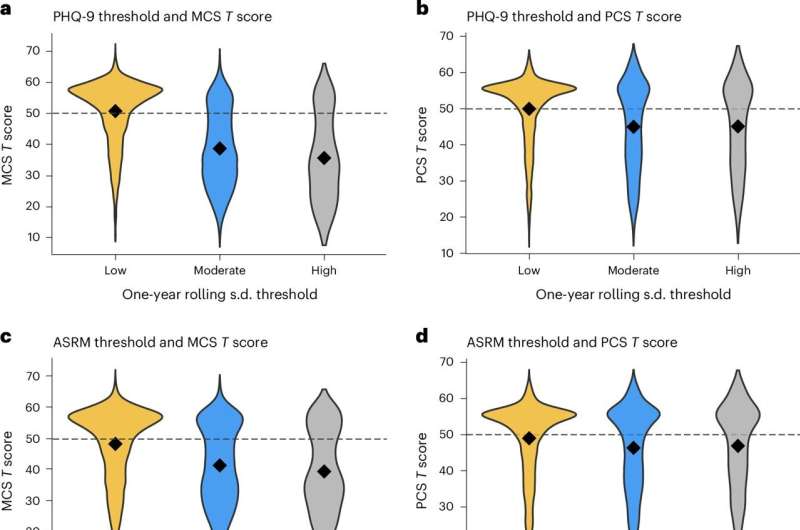

Relationship between one-year moving SD thresholds and mental and physical health. Source: Nature Mental Health (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s44220-024-00291-5

When Dr. Sarah Sperry meets with her patients with bipolar disorder, she asks them what aspect of their illness most impacts their lives.

Many of them say it is due to their lack of control over how strongly they react to events and situations.

However, treating these subtle mood swings and emotional reactivity was not the usual treatment goal for people with this disorder worldwide. Rather, the focus was explicitly on preventing severe depressive, hypomanic or manic episodes.

Part of the problem is that instability is difficult to measure with a standardized questionnaire about current symptoms, nor is it easy to determine how well this variation responds to medications and psychotherapy.

Sperry and his colleagues at the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Michigan School of Medicine now believe they have found a way to do this. They previously studied more than a decade of data from nearly 400 people with bipolar disorder and more than 210 people with other mental illnesses or no psychiatric diagnosis.

They have published their findings from the Prechter longitudinal study on bipolar disorder in Nature Mental Health.

They concluded that it is more valuable to examine trends in these self-reports over time to see how much variation there is within the individual, rather than just looking at a person’s self-reports at one point in time.

Or worse, observe how much they deviate from their normal mood or how large their “spikes” are and work to reduce the size of those spikes through proven or experimental treatments.

“We suspect that the primary outcome measure used to measure the success of clinical treatment or the effect of an experimental intervention may be the wrong one,” says Sperry. “As the patients tried to tell us, it seems to be variation, reactivity and instability that play a role. Now we believe we have a way to measure this.”

Sperry and her colleagues examined data from hundreds of questionnaires that each participant completed about every two months for at least 10 years. These included the PHQ-9 for depression, the ASRM for mania, the GAD-7 for anxiety and the SF-12, which measures quality of life and includes questions about mental and physical health.

They found that people with bipolar disorder were far more likely to experience large fluctuations over time, indicating greater mood instability, than people with other mental illnesses and people without psychiatric illnesses.

They then analyzed the PHQ-9, ASMR, and GAD-7 patterns for each person over time. They found that the more frequently and more these values varied (measured with the SF-12), the worse the psychological and often also the physical quality of life of a person with bipolar disorder was.

By looking at moving averages and deviations for each person over a year, the team created a scoring system that essentially predicts quality of life based on how much each person deviates from their average over time.

And because the questionnaires are short and can be completed quickly via a smartphone app or website, it may be possible in the future to obtain data on patients and clinical trial participants more frequently and to calculate their scores using less than a year of data.

Sperry and his colleagues hope that their scoring system for bipolar symptom variability can be tested using data sets from other studies and large data sets of electronic health records. If it proves effective, they hope it can help better measure the effects of treatments and clinical research and help patients achieve a better quality of life.

They have published the code needed to calculate the variability score for individuals.

“It’s easy to calculate and is based on existing, well-validated questionnaires,” she says. “Variability is central to the experience and everyday functioning of people with bipolar disorder. We need to measure it and work to change the intensity of these fluctuations as a measure of treatment effect.”

In addition to Sperry, the study’s authors include Melvin McInnis, MD, director of the Heinz C. Prechter Bipolar Research Program, where the Prechter Longitudinal Study is being conducted, and Anastasia Yocum, Ph.D., data manager for the research program.

The Prechter Longitudinal Study includes people with bipolar disorder as well as people without mental illness or close relatives with mental illness to serve as comparison subjects. You can find more information here.

Further information:

Sarah H. Sperry et al., Mood instability metrics for stratifying individuals and measuring outcomes in bipolar disorder, Nature Mental Health (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s44220-024-00291-5

Provided by the University of Michigan

Quote: A new method for measuring bipolar disorder: Focus on the “spikes” (August 9, 2024), accessed August 9, 2024 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-08-bipolar-disorder-focus-spikes.html

This document is subject to copyright. Except for the purposes of private study or research, no part of it may be reproduced without written permission. The contents are for information purposes only.